History of the Park

The garden

The English Garden in Palermo (1851-1853), an urban park for the new city

Eliana Mauro

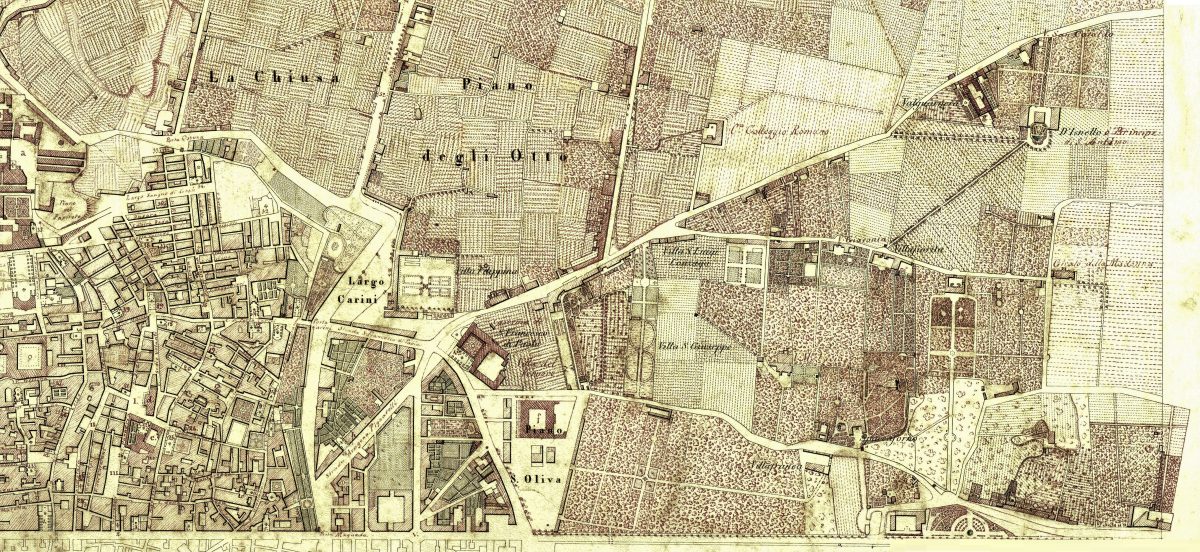

After the eighteenth-century, the season of the great parks of the Palermitan aristocracy was identifiable as the founding elements of the Enlightenment landscape outside the city due to the coexistence of the components of the “useful” and the “pleasurable”. The first half of the nineteenth century saw a proliferation in Palermo of private pleasure gardens with an informal layout, i.e. free of the need to create axial perspectives and geometric forms. After the mid-century era, the “romantic” culture, which cultivated the artistic landscape of garden design, overtaking the contradictory nature of components linked to the informal nature of “rational” thought, expressed by the terms of a new landscape aesthetic which found its own substratum in the neoclassical matrix of the Palermo garden.

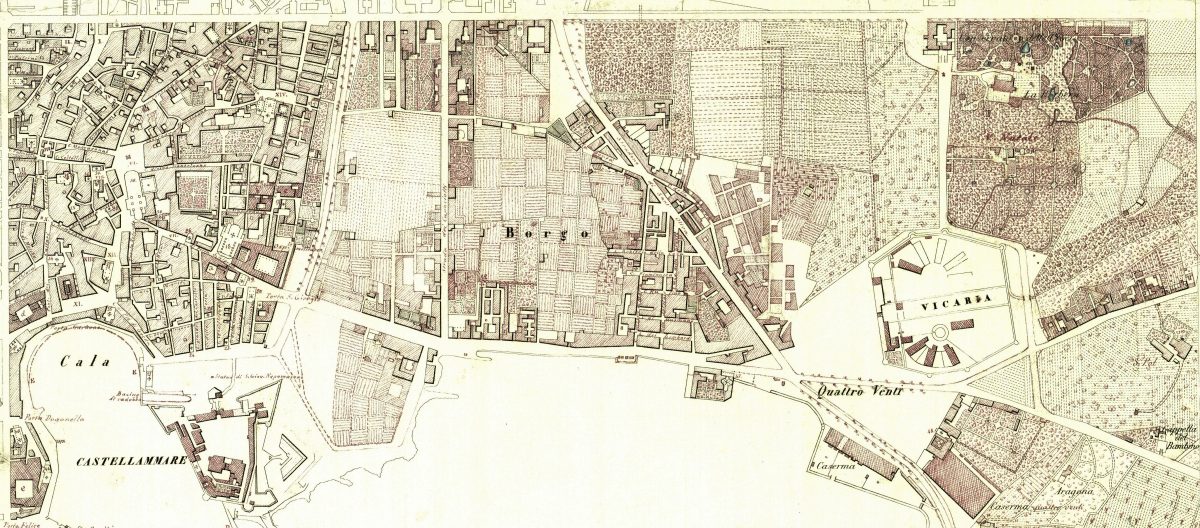

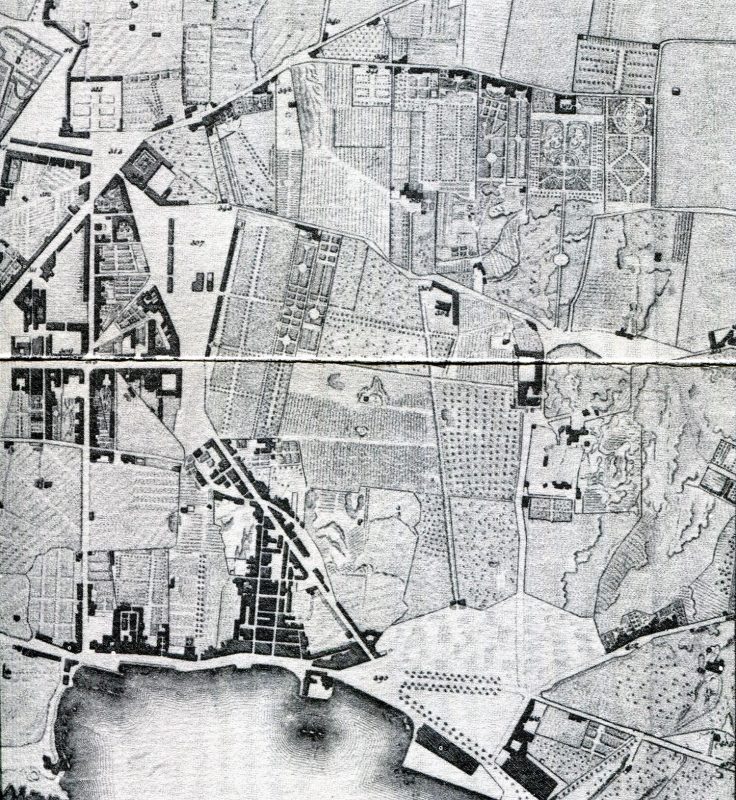

In the landscape of the seafront of the city of Palermo, the Villa Giulia, the “public parterre” par excellence, created in the French style 1, had dominated since 1777.

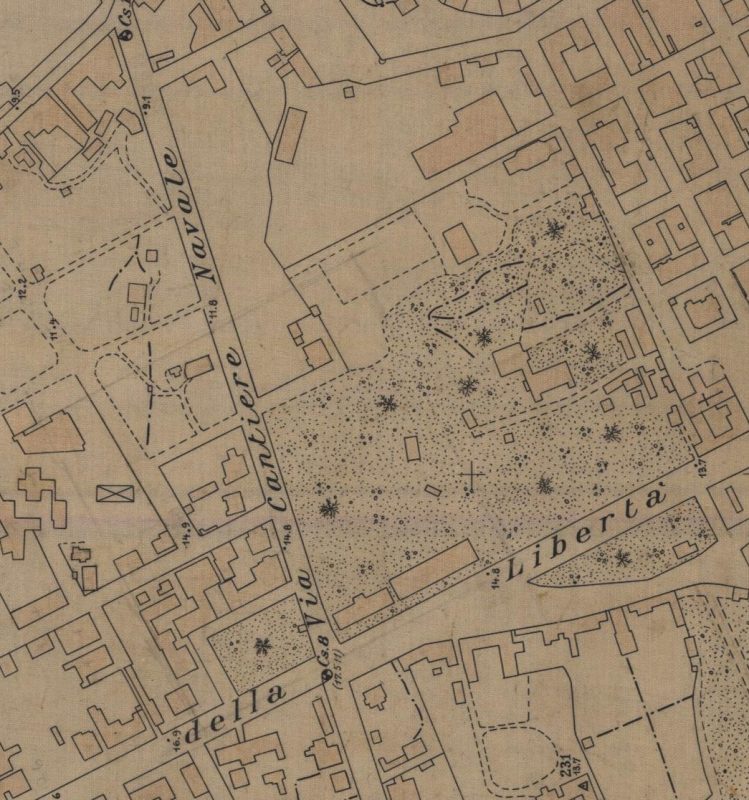

The events of the Risorgimento distinctively affected the future of urban development northwards through the creation of an important road axis, Via della Libertà, and another public garden, the English Garden, designed and created by Giovan Battista Filippo Basile (Palermo, 1825-1891) in collaboration with his master of academic studies, Carlo Giachery (Padua 1812-Palermo 1865) and his patron, the director of the university Botanical Garden, Vincenzo Tineo (Palermo, 1791-1856).2

The planting of a new public city garden paved the way for the application of new naturalistic theories that were also experimented in the field of painting, 3 offering the opportunity to “modernize” new urban expansion with the introduction of a park that became the field of experimentation for the planting of new species, often newly introduced and to be used in private gardens.

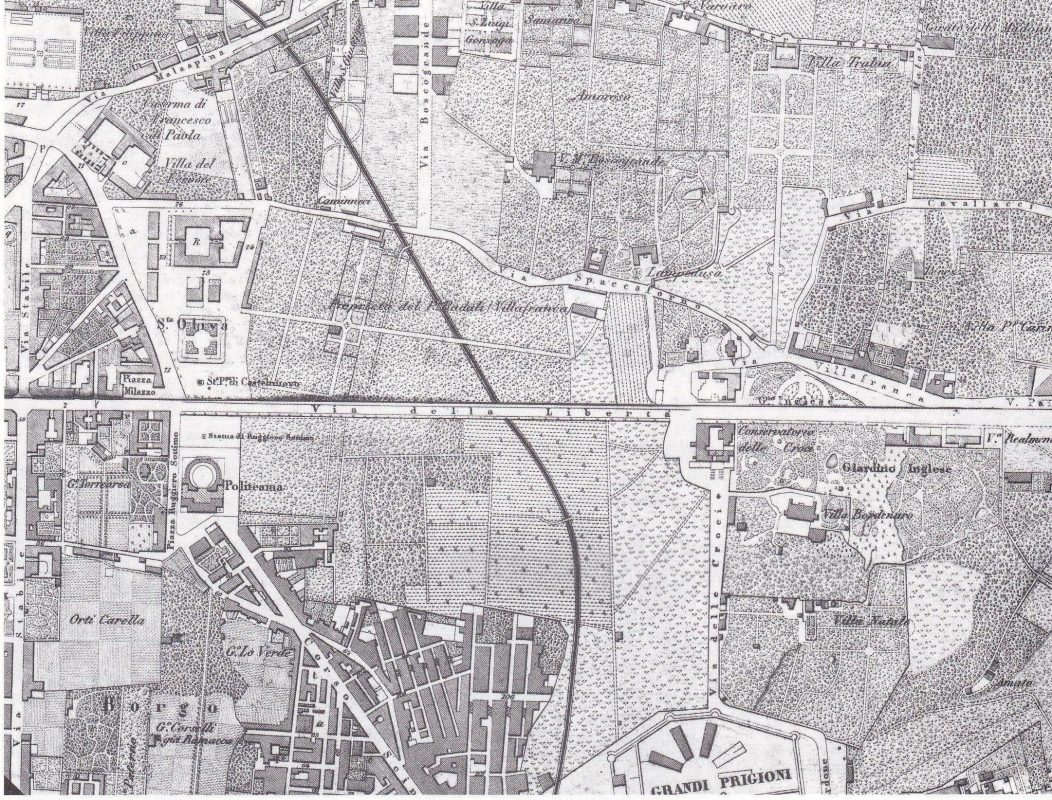

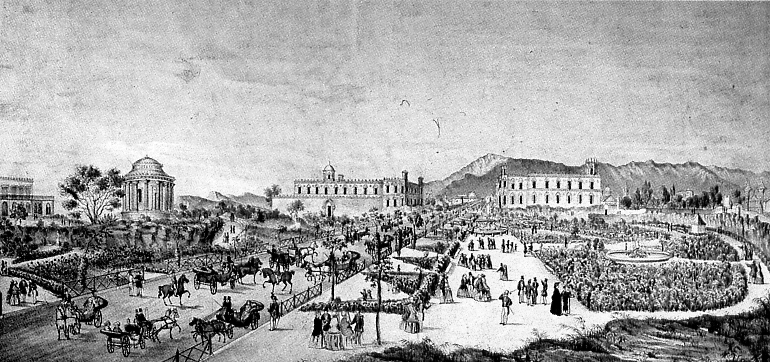

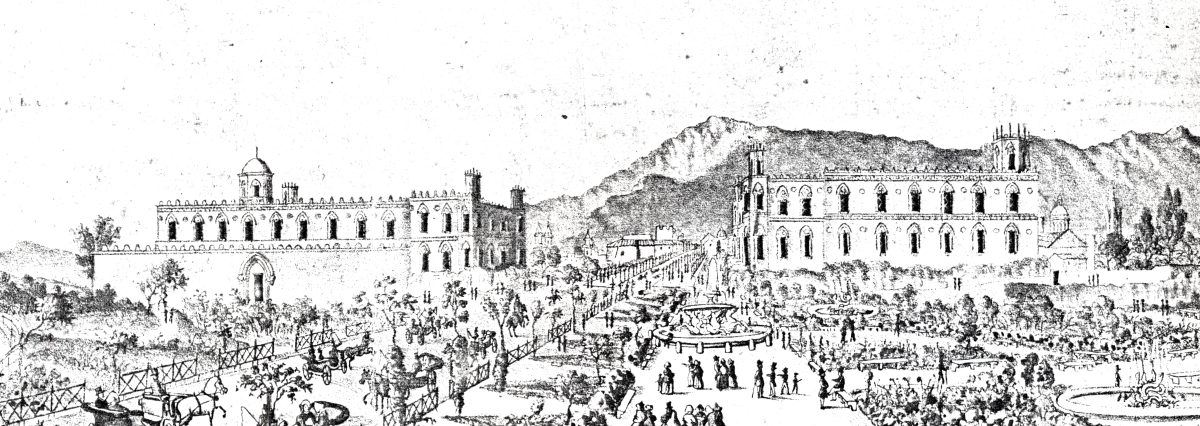

The first section of the Via della Libertà and the English Garden emerged in perfect symbiosis and landscape gardening for several decades from 1851 onwards. The terminal of that street proved similar within the intentions of those who had conceived it – to a Parisian boulevard.

The garden was proposed as an alternative to the large private parks of the aristocracy and its realization for the city, provided a great opportunity destined to exert a radical influence on its urban development as a driving force for future expansion. In anticipation of the construction of a district with multi-story buildings for the new bourgeoisie, the garden represented a practice of implementation of the idea of appropriating the countryside outside the city gates.

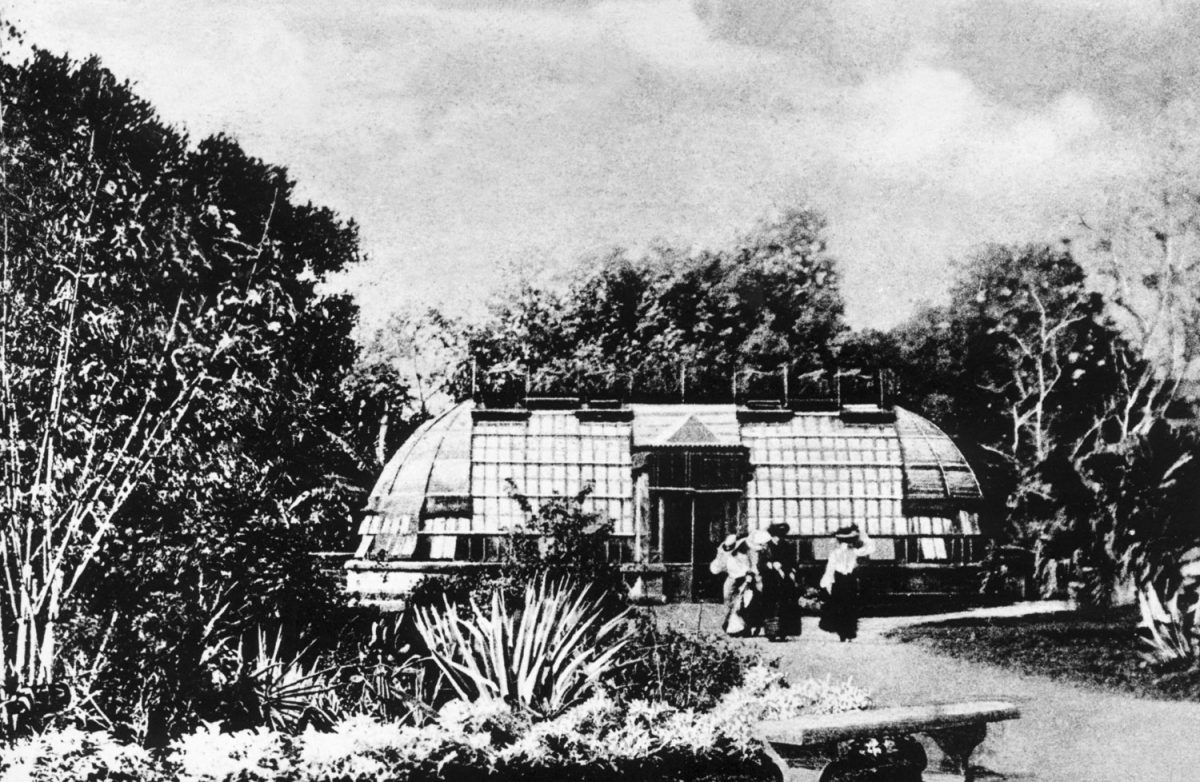

A formulized group of specialists from different disciplines were called upon to oversee the design and realization of the new garden which included Vincenzo Tineo (botanist), Carlo Giachery (architect expert in utilitarian constructions and new technologies) and, later, Giovan Battista Filippo Basile. The formulation of a vastly innovative nature for the city must be related to the two most important civic institutions for controlling and managing urban development: the Building Council, established in 1842, the Municipal Architectural Corps, established in 1856, and finally the Technical Building Office, which followed in 1863 and in which Basile held the position of Chief Engineer. 4

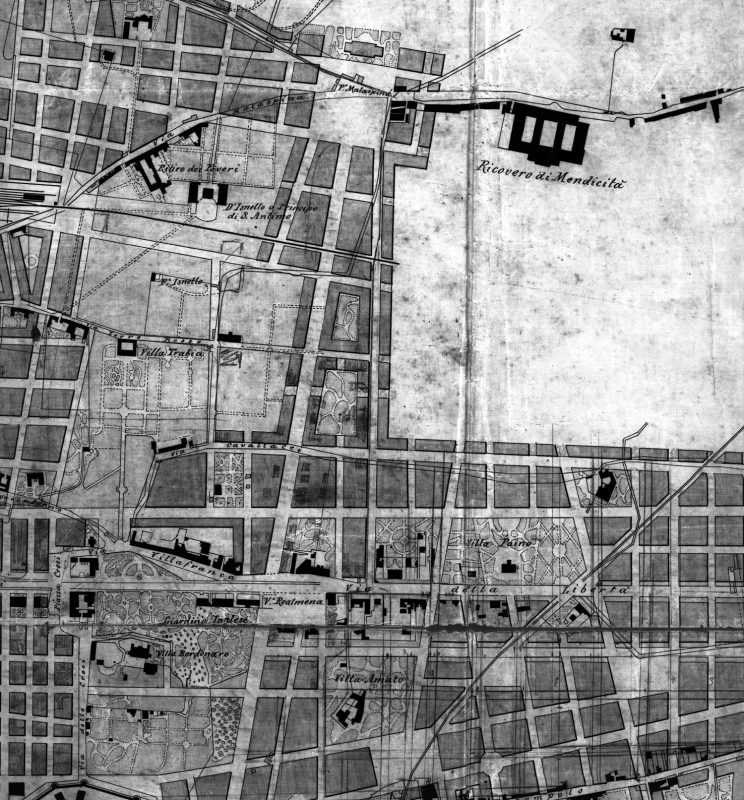

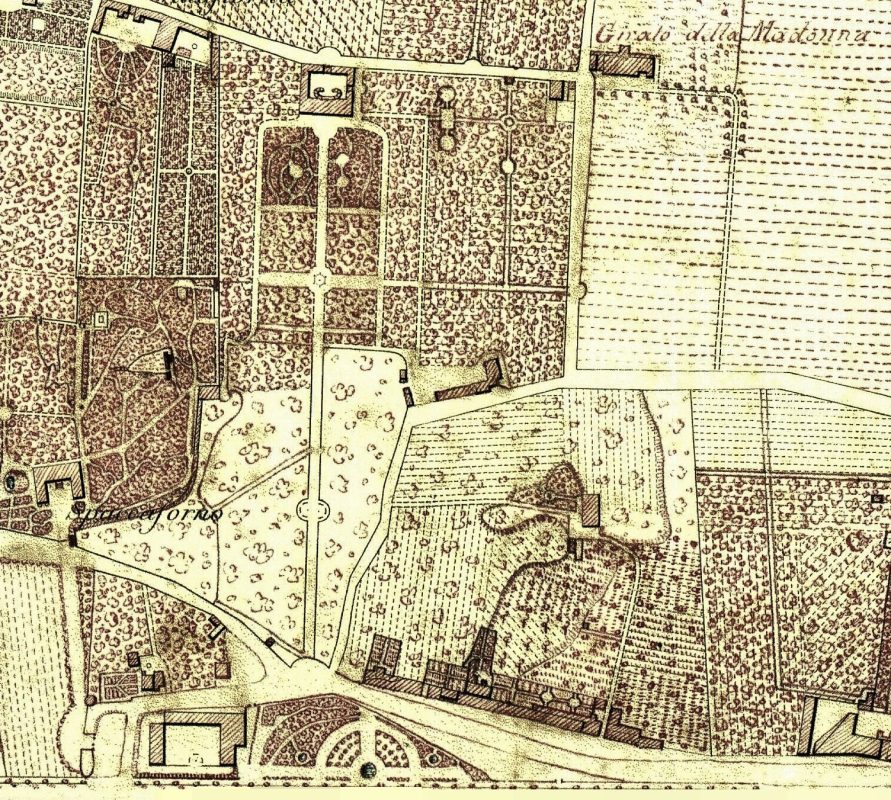

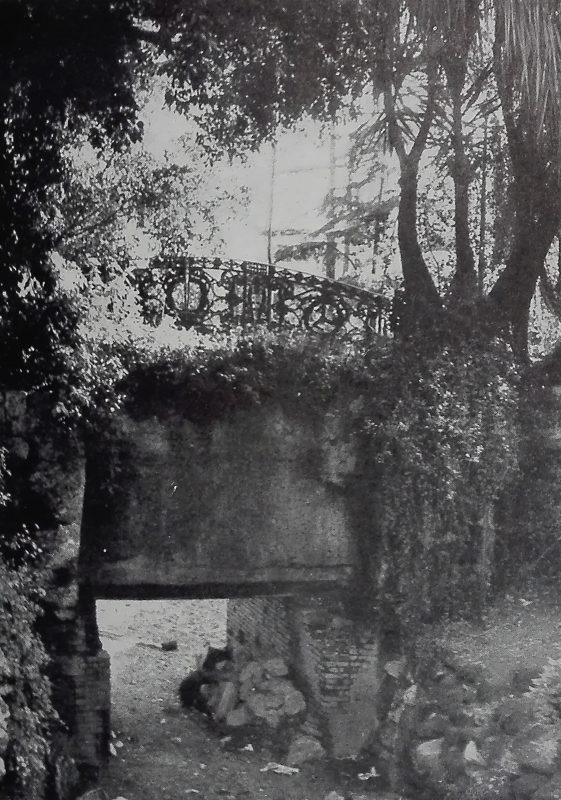

For the construction of the road, a deep cut had to be made in the calcarenite rock that reconstructs the geomorphological plane of the city in several places raised above the plane of the road idealized to be built. The stones were reused in the building activities of the garden, but the most characteristic element of the area remained in its very irregular elevation.

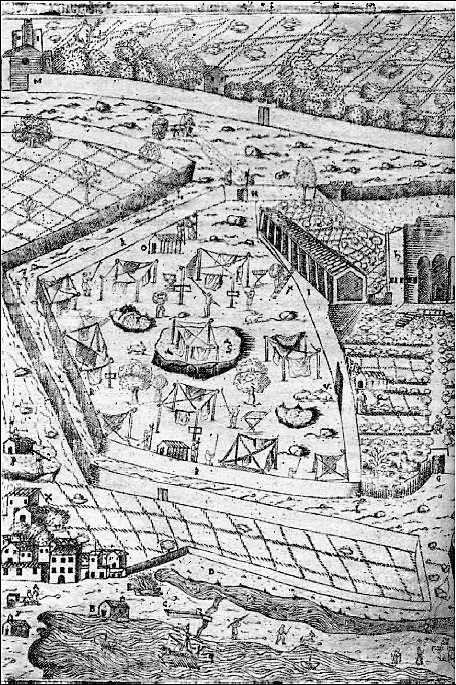

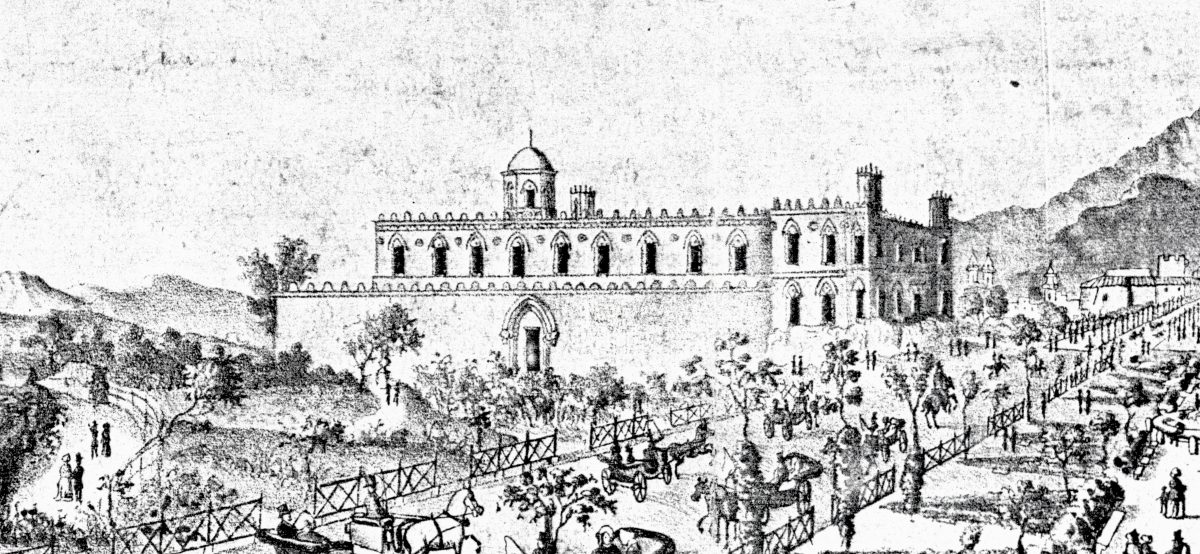

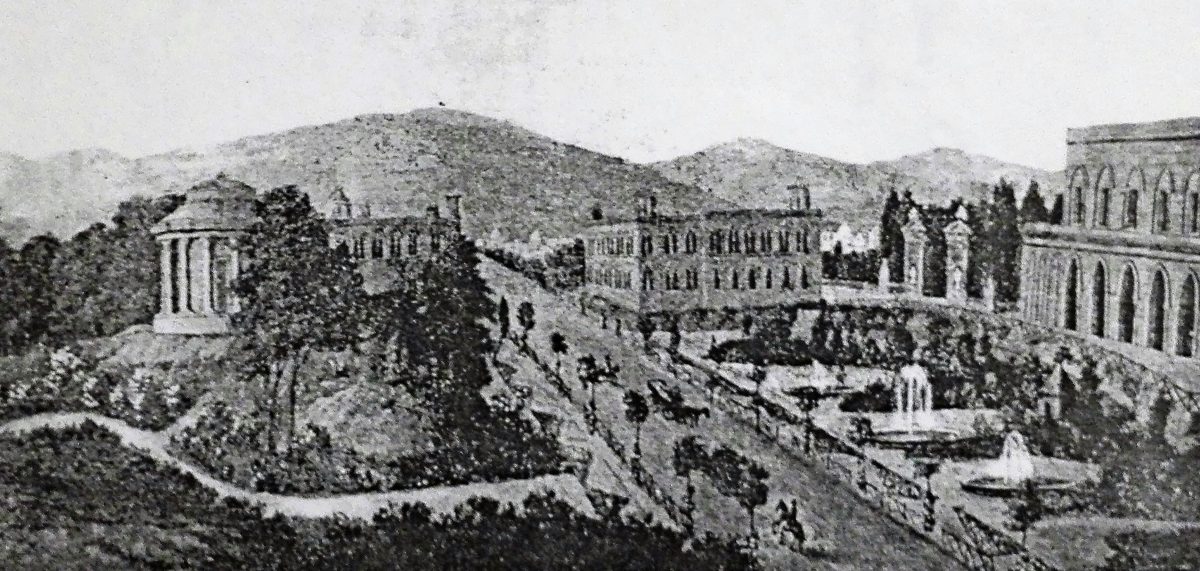

Exploiting the characteristics of the terrain, G.B.F. Basile organized an authentic historical-symbolic orchestration, alluding to an emiral island government that had been historically renowned for its tolerance, livability, caves and natural ravines to give shape and meaning to the English-style public garden.

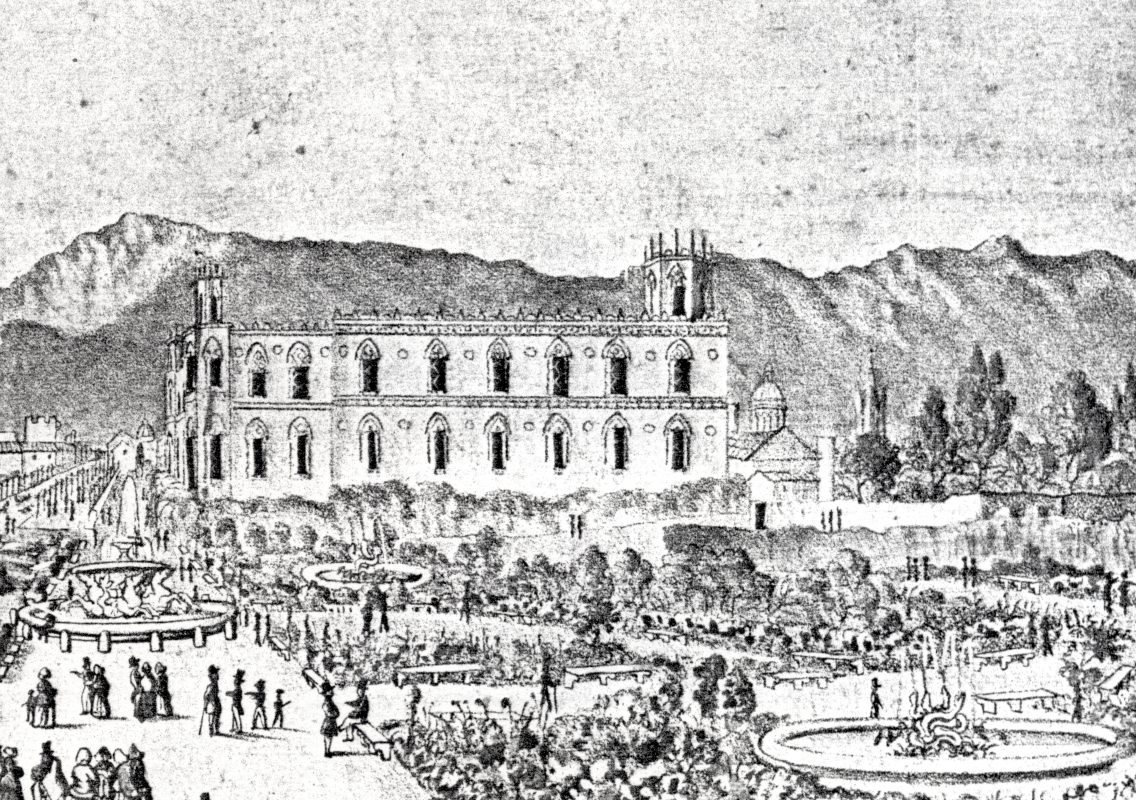

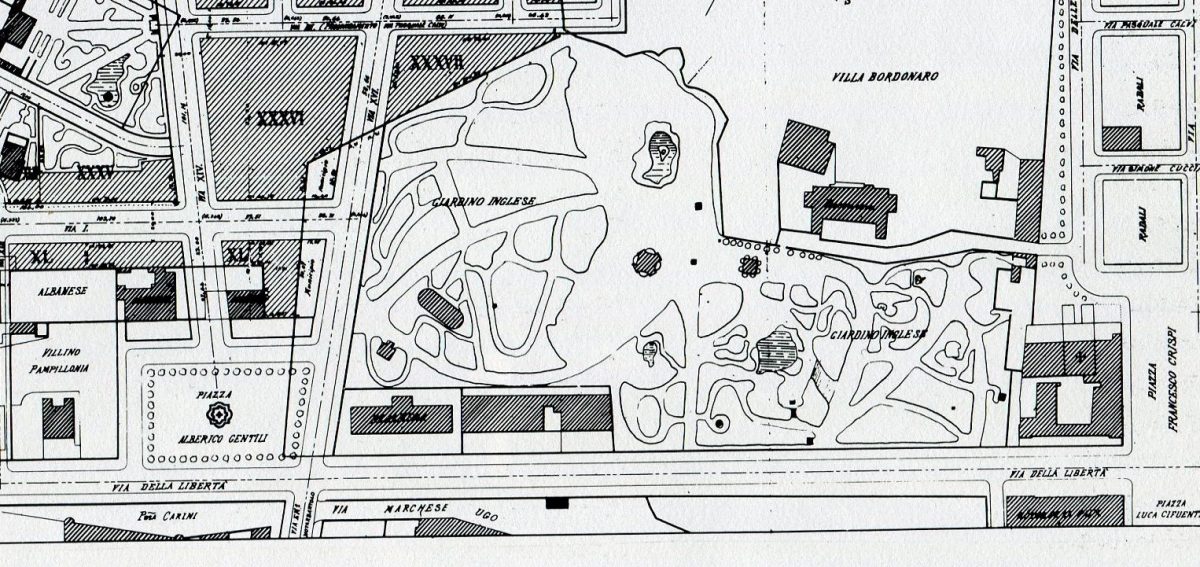

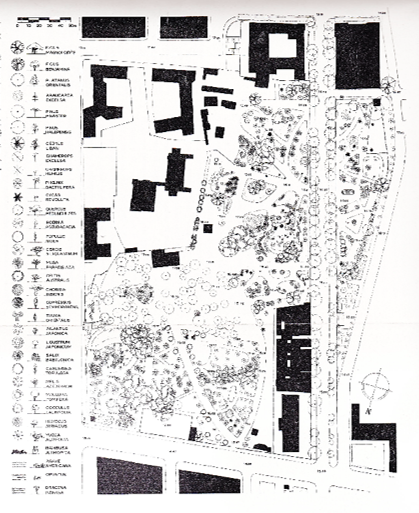

The main division of the garden stems from its topographical position crossed by the new street and the physical components that straddling it. The garden will consist of two parts of different sizes &sides: The Forest, the former “garden of delight of the Emir Al Achal”, being large and hilly on the right of the street. To the left is the Parterre, the “modern” part of the garden being much smaller and on a single levelt. At the time of its realization, Basile would ensure that the street and the garden would appear as a single organism incorporating the areas destined for small gardens in the front of the homes into the overall arrangement and postponing the realization of the future fence (whose grating, removed for the “iron to the homeland” operation, would be replaced in the post-war years with the present one).

In the Sheet of explanations that accompanied the project, drawn up by Basile in 1850, the theme of “the Emir Al Hachal’s” garden dominates. It is the pretext to present the Forest as a “restoration of ancient delight” and to introduce the hypothetical existence of Arab and Greek architecture.

The Forest will be divided into seven promontories, places titular to epochs or historical figures: the Pagoda (first); the Castle and Saracen Tower (second); Archimedes (third); Psyche (fourth); the Temple of Vesta (fifth); Nina, the 13th-century Sicilian poetess (sixth); and the Hut (seventh). Each promontory is bordered by one or more valleys in a number of ten and aggregates caves and natural galleries in while each landscape environment is assigned the appropriate tall tree species and herbaceous plants.

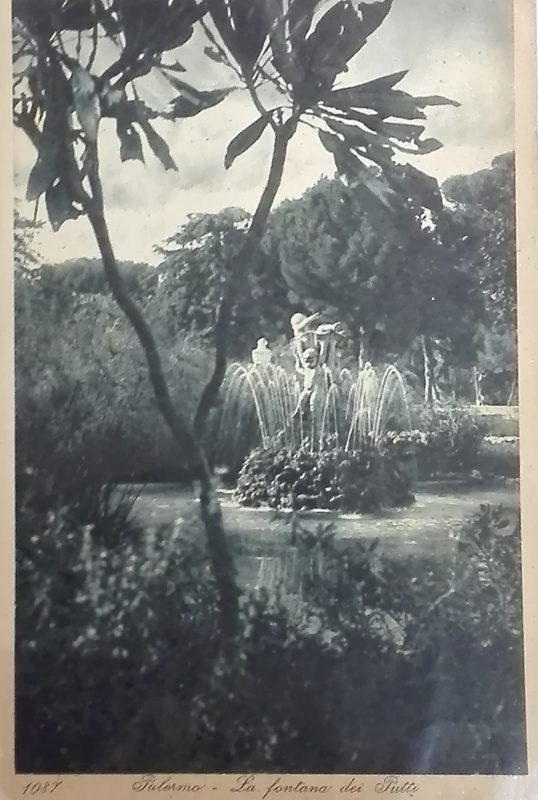

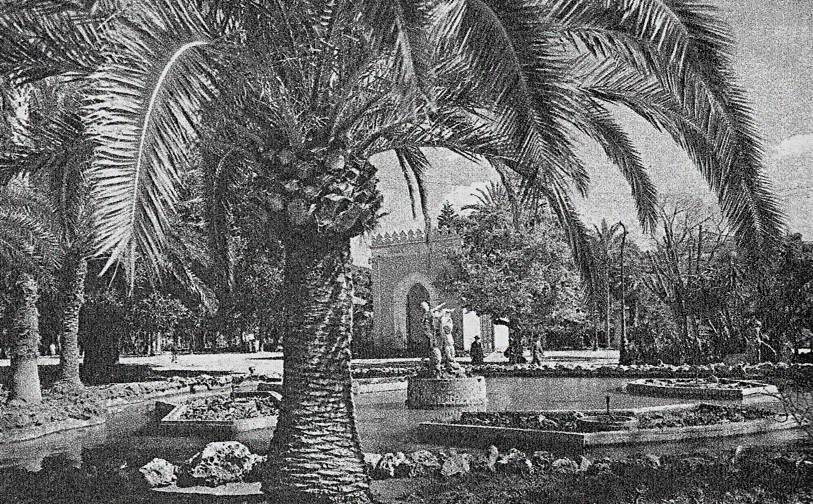

The Forest, on the side of the maximum extension to the urban promenade, as well as, on the opposite side of the road. The “modern part” of the garden, is the Parterre, which is less extensive and designed in parterres, consisting of a grotto, grove and fountains. 5

The “Direction of the Royal Botanical Garden and Public Plantations of Palermo”, directed by Vincenzo Tineo, from which depicted the realization of the entire urban section ; the two parts of the garden, the street, the restoration of the façade of the Prison of the Crosses, demolished for the construction of the street, the restyling of the few existing houses bordering the garden , the scientific-botanical choices, the garden’s furnishing of a great variety of flowering plants and large number of trees. Ever selection was carefully chosen and shared by the designer, suited to his design choices and with the attribution of naturalistic habitats to each hill and valley created. 6

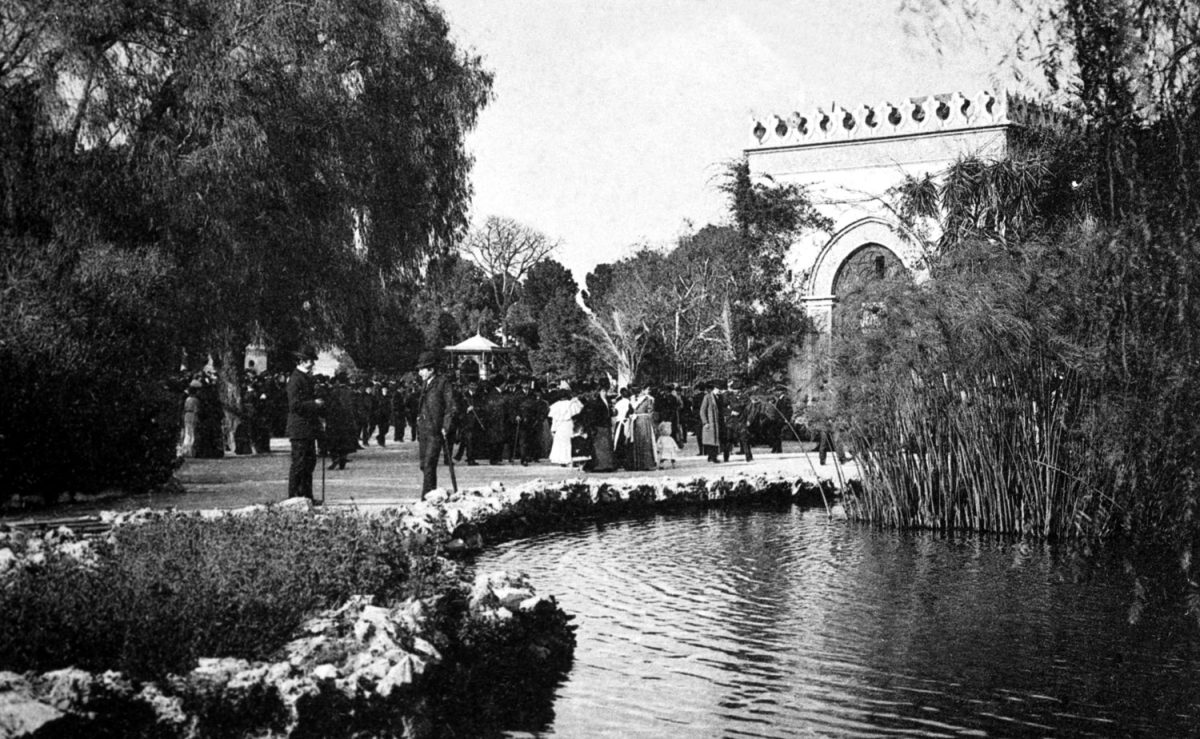

The altimetric variations obtained by Basile, still allow for detailed views even below street level, despite the transformations carried out around the 1930s; the garden’s attractiveness is based on the elements of surprise that multiplied the spaces and cultivated species in the transition from the valleys to the grottoes, the summits and of the promontories. The enjoyment of Parterre, on the other hand, springs from the coplanarity of the entire space enclosed by the natural “cliff”, but also from the views from the top of the rock face 7, where the Marchese Ugo street is realized. 8

Conceived on the model of the Parisian boulevards 9, with a central carriageway enriched by two rows of plane trees and two driveways on either side and wide pavements, Via della Libertà had the new public garden as its goal until almost the end of the 19th century.

Having been created as a “new destination for a new city 10, the English Garden could hardly have maintained its character as a backdrop, though the work undertaken to regularize and extend Via della Libertà did not immediately have the desired effect. It was necessary to wait until the pavilions of the first Sicilian Agricultural Exhibition 11 which were built in 1902, designed by Ernesto Basile, a few dozen meters from the northern boundary of the garden. The ephemeral arrangement provided for a bridge/gateway thrusted between the two road margins and an entrance pavilion, to the side, behind which were the areas of the various exhibition sectors. The building and the bridge, with its clear modernist features, ferried the street towards the extension and its final destination in the master plan, and even though this second long stretch of the street had the roadway reduced to a single carriageway, the character of a street lined with rows of plane trees and flanked by gardens and tree-lined squares still remains its distinguishing feature 12.

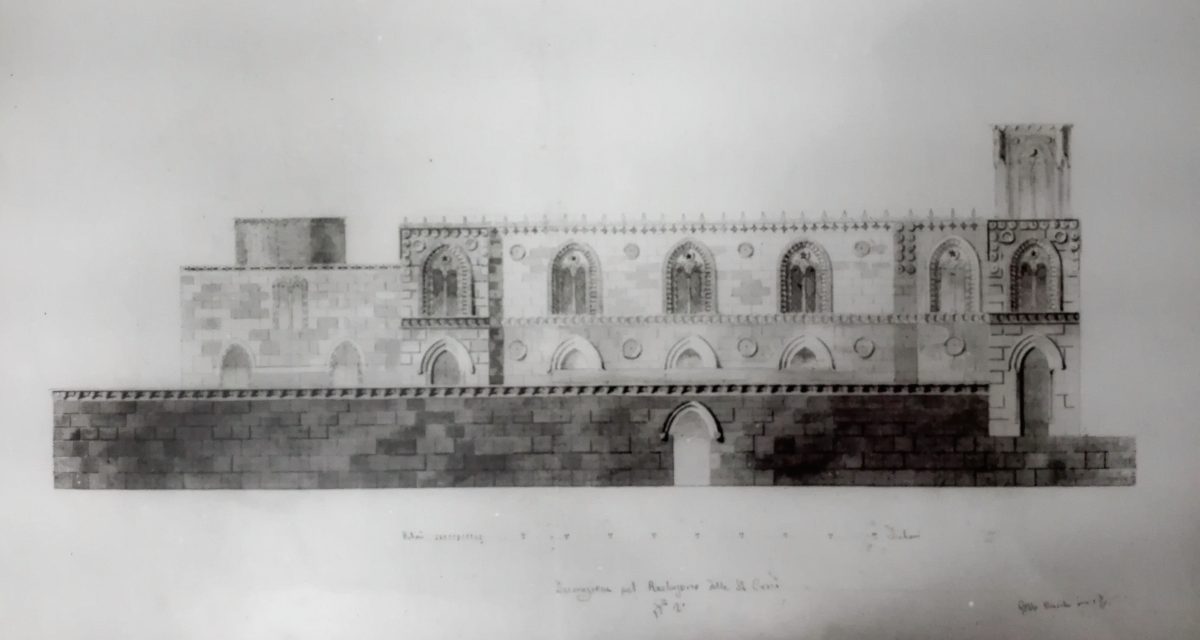

In designing the garden, G.B.F. Basile, remained with his thoughts on modern architectural lines, also envisaged that the new residential quarter, which would rise along the street and around the English Garden, would be a renewed example “of mediaeval architecture”, and proposed it, almost as a prototype of his idea, for the reconstruction of the façades of the adjoining Prison of the Crosses 13.

The body of the conventual structure bordering the garden, consisting of three wings and the church of Santa Maria di Monserrato which leaned against the east side and obtained from the central rooms of the ancient Renaissance villa, which had in fact been mutilated by cut for the construction of the road and left without a façade in correspondence with the new street. This would be an opportunity for G.B.F. Basile to configure a façade with a pointed arch and stepped openings, resting on top of the exposed limestone rock relief that can still be seen today, and that evokes his vision of those renewed medieval forms that would have represented the “missing link” and resolved the contradictions between “ancient” and “modern” in architecture 14.

Download Full Version (Pdf 6.3 MB)

1 La proposta progettuale di un nuovo quartiere d’abitazioni con una grande piazza emiciclica interamente porticata era stata redatta, a ridosso della Villa Giulia e appena due anni dopo l’avvio dei lavori per il suo impianto, da Girolamo Carena su commissione e ideazione di monsignor Giuseppe Gioeni. Il progetto, la cui incisione acquarellata si conserva presso l’Archivio Storico del Comune di Palermo, mostrava, così come era nelle intenzioni dell’ideatore, la matrice utopico-riformista di tutto il suo pensiero. Per le opere e la vita di Giuseppe Gioeni si veda E. Mauro, Giuseppe Gioeni (1717-1798): Pensiere Platonico e Carta Geografica della Sicilia, in Centro Studi di Storia e Arte dei Giardini, L’isola iniziatica. Raccolta antologica dal Seminario Internazionale, Capo d’Orlando, Villa Piccolo 9-10 ottobre 1986, Palermo 1990, pp. 51-66, e dello stesso autore Giuseppe Gioeni, in Luigi Sarullo, Dizionario degli artisti siciliani. Architettura, Novecento Editrice, Palermo 1993, pp. 209-210.

2 Si vedano, per il Giardino Inglese, per tutti, i volumi: Gianni Pirrone, Michele Buffa, Eliana Mauro, Ettore Sessa, “Palermo, detto paradiso di Sicilia” (Ville e giardini, XII-XX secolo), Centro Studi di Storia e Arte dei Giardini, Palermo 1989, pp. 187-197; Giuseppe Di Benedetto, Ettore Sessa, Dalla Strada della Real Favorita alla Villa Deliella. La misura della qualità nella prima espansione settentrionale di Palermo, con testi di Eliana Mauro e Angela Persico, 40due Edizioni, Palermo 2022, pp. 150-203.

3 Sarà così per la città di Caltagirone, in provincia di Catania, dove l’anno dopo Basile verrà chiamato per dare carattere e compimento paesaggistico al giardino pubblico comunale. Si veda S. Bruno, Il giardino comunale di Caltagirone di G.B. Basile, Centro Studi di Storia e Arte dei Giardini, Palermo 1990.

4 Il Consiglio Edilizio viene istituito con Regio Decreto del 29 maggio 1842, il Corpo Architettonico municipale viene istituito con Regio Rescritto dell’11 febbraio 1856. Si veda F. Meli, Degli architetti del Senato di Palermo nei secoli XVII e XVIII, in “Archivio Storico Siciliano”, 1939, IV-V, pp. 351-352, 354. Per un profilo biografico dei personaggi citati, si veda, alle rispettive voci, Luigi Sarullo, Dizionario degli artisti siciliani. Architettura, cit.

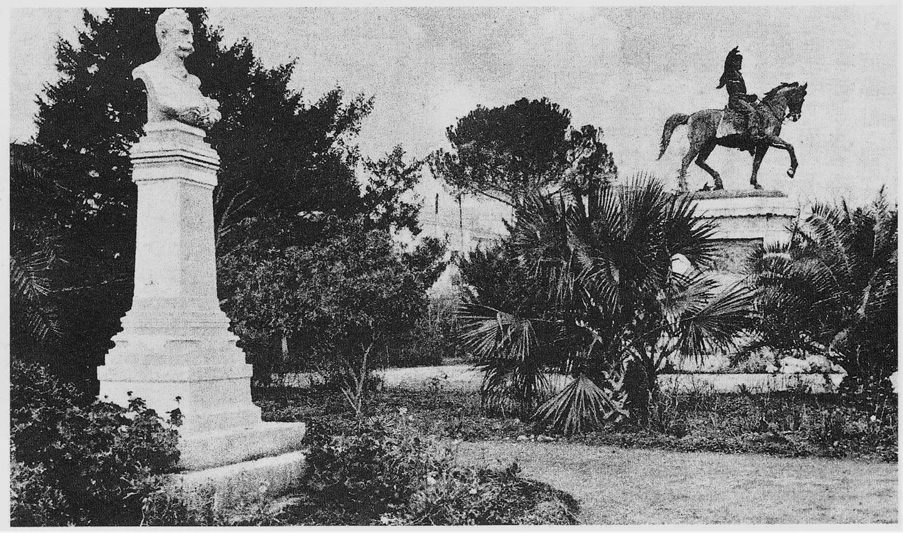

5 Il Bosco (considerato dalla cittadinanza il vero e proprio Giardino Inglese) è oggi dedicato alla memoria di Piersanti Mattarella; il Parterre è stato invece dedicato alla memoria di Giovanni Falcone e Francesca Morvillo. Al centro del parterre è stato collocato nel 1892 il monumento equestre in bronzo di Giuseppe Garibaldi di Vincenzo Ragusa, su un alto podio marmoreo con scene in bronzo sbalzato e un leone accovacciato alla base di Mario Rutelli, per il quale per più di un secolo ebbe attribuito il nome di Giardino Garibaldi. Si vedano: Luigi Sarullo, Dizionario degli artisti siciliani. Scultura, Novecento Editrice, Palermo 1994, alla voce; Eugenio Rizzo, Maria Cristina Sirchia, Scultori siciliani. XIX e XX secolo, Dario Flaccovio Editore, Palermo 2009.

6 Si veda Gianni Pirrone, Michele Buffa, Eliana Mauro, Ettore Sessa, Palermo detto “paradiso di Sicilia”. Ville e giardini (XII-XX secolo), Centro Studi di Storia e Arte dei Giardini, Palermo 1989.

7 Le notizie e i documenti citati e quelli consultati riguardo alla realizzazione del giardino e alla scelta di piante e reperti che si trovano dentro il giardino sono reperibili presso l’Archivio di Stato di Palermo, Ministero e Real Segreteria di Stato presso il Luogotenente Generale in Sicilia, Rip. LL.PP., vol. 1370, fasc. 36, vol. 1429, fasc. 3.

8 Comune di Palermo, Atti del Senato, IV Comitato dell’Interno, Istruzione Pubblica e Commercio, Deliberazione del 16 marzo 1848.

9 Il riferimento al modello della capitale francese è attribuito ad Emanuele Palermo, componente dell’Ufficio Tecnico Edilizio del Comune, che ne curò il progetto e ne diresse i lavori secondo le notizie riportate nella commemorazione che ne fece un suo allievo, Melchiorre Minutilla, pubblicata nel 1880, volume II, degli Atti del Collegio degli Ingegneri e Architetti di Palermo.

10 Gianni Pirrone, Miti e riti della passeggiata: la strada della Libertà e il Giardino Inglese, in Gianni Pirrone (a cura di), Palermo, una capitale. Dal Settecento al Liberty, con testi di Eliana Mauro ed Ettore Sessa, Milano, Electa 1989, p. 41

11 Per le opere di Ernesto Basile si veda Ettore Sessa, Ernesto Basile. Dall’eclettismo classicista al modernismo, Novecento Editrice, Palermo 2002.

12 La via della Libertà, nella sua interezza realizzata tra il 1848 e il 1909, frutto di due successive estensioni, procede in rettilineo dall’estremità nord dell’ampliamento settecentesco fino a coprire tutta la previsione di ampliamento nord del Piano Regolatore del 1886, per circa due chilometri e mezzo. Si vedano: Salvatore M. Inzerillo, Urbanistica e società negli ultimi duecento anni a Palermo. Piani e prassi amministrativa dall’«addizione» Regalmici al Concorso del 1939, Quaderno 9, Istituto di Urbanistica e Pianificazione Territoriale, Università di Palermo, Palermo 1981; Idem, Urbanistica e società negli ultimi duecento anni a Palermo. Crescita della città e politica amministrativa dalla “ricostruzione” al piano del 1962, Quaderno 14, Istituto di Urbanistica e Pianificazione Territoriale, Università di Palermo, Palermo 1984. Per il rapporto tra la strada e i suoi numerosi traguardi si veda Eliana Mauro, L’ampliamento della città di Palermo all’inizio del Novecento: il fondale celebrativo di via della Libertà come scambiatore tra tessuto urbano e parco paesaggistico, in «Storia dell’urbanistica», n. 15, 2023, pp. 200-213.

13 Il disegno è pubblicato per la prima volta in Gianni Pirrone, Michele Buffa, Eliana Mauro, Ettore Sessa, op.cit., p. 195. Si vedano i lavori a stampa pubblicati sullo studio e sugli svolgimenti dell’architettura da Giovan Battista Filippo Basile: Metodo per lo studio dei monumenti, Stamperia di M. Console, Palermo 1856; Osservazioni sugli svolgimenti della architettura odierna all’Esposizione Universale del 1878 in Parigi. Proposte di riforma nell’insegnamento relativo. Relazione di G. B. F. Basile giurato per la Classe IV, Palermo 1879; Curvatura delle linee dell’architettura antica con un metodo per lo studio dei monumenti. Epoca dorico-sicula. Studi e rilievi di G. B. F. Basile, Tip. del giornale “Lo Statuto”, Palermo 1884.

14 La periodizzazione dell’architettura attraverso le epoche storiche a cui fa capo la teoria dell’”anello mancante” viene pubblicata per la prima volta da G.B. Filippo Basile nel Metodo per lo studio dei monumenti, Stamperia di M. Console, Palermo 1856.